Recently I wrote a detailed response in an audio engineering group where a user was asking why his pitch correction software was having trouble with tuning his raspy singing. Since I already went through the trouble of writing it out, I thought I’d share it as a here as well as I guess many singers could potentially be interested. So here’s the copy-paste:

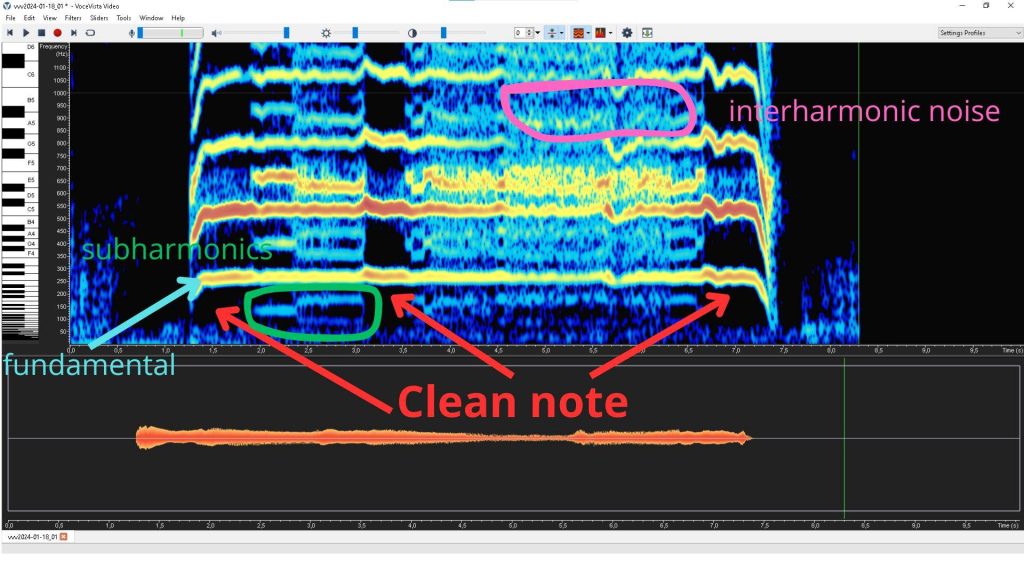

If you analyze raspy vocals with a spectrogram compared to a clean vocal, you’ll notice the raspy vocals will have lines between the harmonics. Adding rough vocal effects (rasp) will add subharmonics below the fundamental and sometimes those subharmonics aren’t stable and shift around. In my experience, most tuning software will recognize those subharmonics as a fundamental and if the subharmonic jumps around or if the raspiness comes in and out while the singer is actually singing the same pitch, the software will recognize it as a pitch change. Those subharmonics will also have a set of their harmonics visible as the lines between the harmonics of the pitch you’re singing.

On top of that, raspiness also adds interharmonic noise, meaning there’s more noise energy in between the actual harmonics which also makes pitch detection harder.

I’m attaching a spectrogram of a quick raspy example with different subharmonics so you can see what I mean!

And here’s the audio file, so that you can hear it and make more sense of what you see:

So, first I’m starting with a clean note, then I’m using a technique that is called distortion in Complete Vocal Technique. It’s the most common thing people refer to when they talk of “rasp”. The ventricular folds vibrate along with the true vocal folds and modulate the airflow in a way that creates subharmonics. So after the short clean bit, I add distortion to get an octave subharmonic, then jumping to the second subharmonic which is an octave and a fifth (which gives it that almost power chord sounding vibe), then going back to clean sound, then going into a more chaotic subharmonic thingy, then into a version that creates even more interharmonic noise, back into the octave and a fifth subharmonic and finally ending on a clean note again.

I think the most obvious shift you can hear is at the beginning when the subharmonic suddenly drops a fifth below (from around a C to around an F – sorry I didn’t take a pitch reference before, so it’s all about a quarter step sharp).

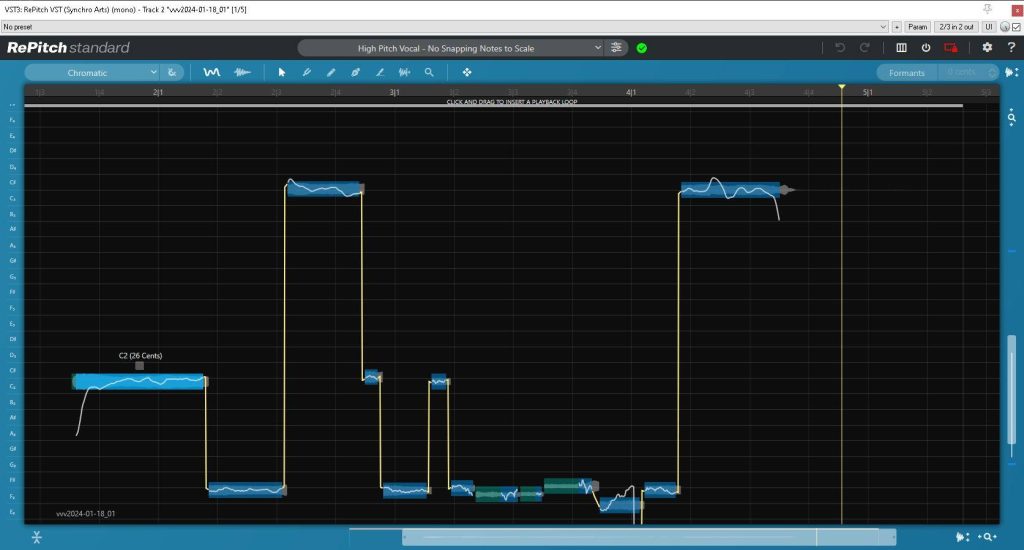

And I’m also attaching how Synchroarts Repitch graphs the pitch of this example! To the human ear it’s very obviously just a single fundamental, but Repitch hears it as a changing fundamental!

Sorry for the lengthy explanation, I’m a nerd! ![]()